This effort is dedicated to the millennial generation.

Like many millennials, my formal education was timed at the peak of the replication crisis. In high school, my AP Psychology course uncritically presented social priming, learning styles, and the Stanford Prison Experiment as scientific facts. Then came various social science theories during my undergraduate years, right as the deluge of replication failures hit in the early 2010s. The experience left me with a lasting skepticism that eventually expanded across all popular science literature.

Even as experimental design improves and replication studies continue, systemic issues remain. Top among them is the asymmetry that splashy new studies make the headlines, while critiques and retractions are quiet footnotes. Shoddy work also tends to ignite debates which are elevated via social media algorithms, garnering the ideas undue prominence and influence. I don't always have the time to evaluate claims and keep up with ideas outside of my expertise.

What To Do?

Fortunately, something changed in 2025: LLM's with built-in web search became genuinely useful for research synthesis. Not "useful" in the demo sense where you prompt it carefully and marvel at the output. Useful in the sense that you can craft a structured task, let it run autonomously, and (with safeguards) get back something that you can actually rely on.

The key capability is agentic tool use: the model decides what information it needs, formulates queries, retrieves results, and synthesizes findings. This is different from retrieval-augmented generation (RAG), where you pre-index a corpus and inject relevant chunks into model context. There is no “right” corpus to pull from. The relevant sources are scattered across journals, preprint servers, and researcher blogs. The queries depend on understanding the specific claims being evaluated. You can't pre-index "everything that might be relevant to evaluating REM sleep impacts" because you don't know what is relevant until the evaluation commences.

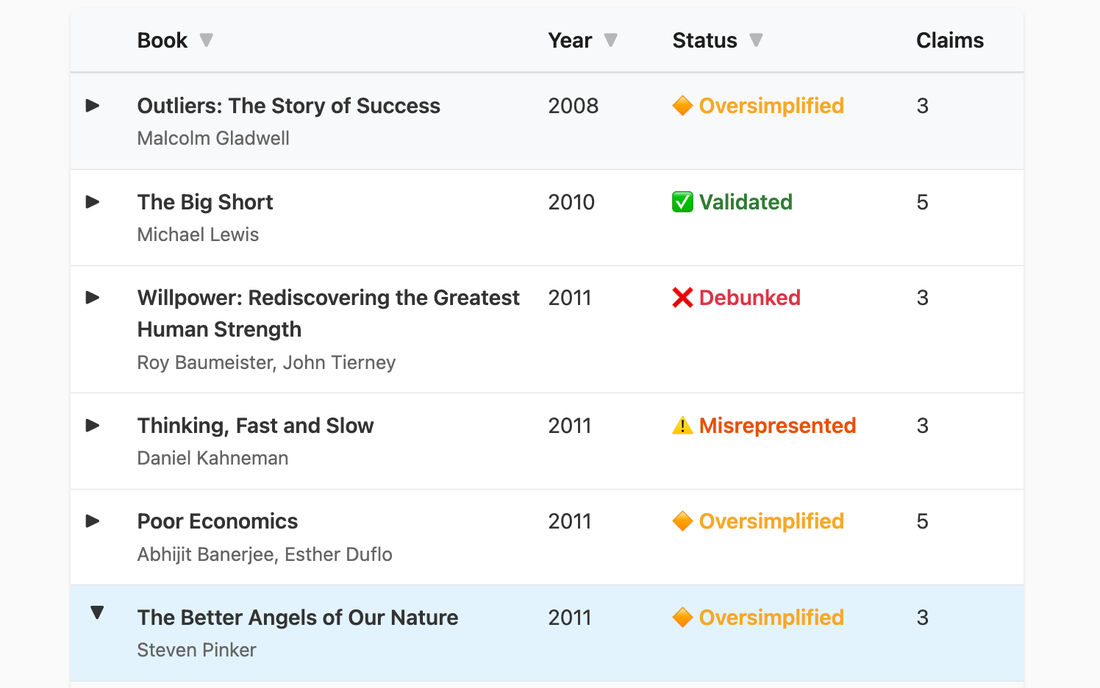

So I built a pipeline that systematically evaluates bestsellers against the replication literature. Click on each entry to review the specific claims, understand key issues, and learn what holds up:

Book Evaluations

Evaluating pop science book claims against the replication literature. Click any row to expand.

| Book ▼ | Year ▼ | Status ▼ | Claims |

|---|

The Architecture

The research pipeline has a few properties that make it interesting from a systems design perspective:

Structured extraction from unstructured sources: Books make claims, cite studies, and suggest interventions. Web sources contain replication attempts, meta-analyses, and expert critiques. Neither is in a convenient format. The evaluation needs to produce structured data—JSON with specific fields for claims, evidence sources, and assessments. Until recently, that meant a defense-in-depth pattern: try to parse JSON from code-fenced blocks first, fall back to finding raw JSON objects, use brace-matching to find complete objects. Fortunately, Claude's tool_use and strict output format beta (Nov 2025) has helped make this a lot easier.

Multi-source synthesis: Evaluating a single claim might require finding the original study, locating replication attempts, checking expert blogs (Gelman, Data Colada), and synthesizing these into an assessment. But the right queries depend on understanding the specific claims being evaluated. Instead, the model receives the evaluation task, has access to web search, and decides what queries to run based on the claims it's investigating. This is sometimes called a ReAct (Reasoning + Acting) pattern—the model alternates between reasoning about what information it needs and taking actions to retrieve it.

Batch processing with reliability constraints: Running 50+ evaluations means you're going to hit rate limits and want to resume interrupted runs. The system implements proactive rate limiting and retries. After each book evaluation, progress is saved in checkpoints. This is standard practice in production systems but often overlooked in research tooling.

The Evidence Hierarchy

Not all sources are created equal. A pre-registered multi-lab replication is stronger evidence than a critical tweet, even if both say the same thing. But you can't just ignore lower-tier sources, because sometimes that's all that exists. And sometimes the hobbyist researcher has done the actual work that the journals haven't caught up to yet.

The evaluation framework encodes this explicitly:

Tier 1 (high quality): Peer-reviewed replications, meta-analyses, retractions, formal academic critiques. This is the gold standard. If a Tier 1 source says a finding failed to replicate, that's authoritative.

Tier 2 (moderate): Science journalism with expert interviews where someone actually called researchers and asked questions. Secondary but useful.

Tier 3 (use with caution): Op-eds, social media, general takes. Sometimes valuable for flagging issues before they hit journals, but not sufficient on their own.

The evaluation prompt instructs the model to prioritize Tier 1 sources and note when assessments rely on lower-tier evidence. This gets reflected in a confidence rating, where high confidence requires Tier 1 sources; assessments based primarily on Tier 2 or 3 sources get lower confidence.

Why does this matter? Without explicit source quality reasoning, you risk a mix of Nobel laureate critiques and random blog posts treated as equivalent. The model has baked-in reasoning and evaluation capability, but we want a consistent rubric.

The Taxonomy Problem

Before you can evaluate claims, you need categories that capture the relevant distinctions. The naive binary of "replicated" or "didn't replicate" misses important nuance. Consider:

Willpower by Roy Baumeister argues that self-control operates like a muscle that gets depleted with use. Two large multi-lab replications (23 labs with 2,141 participants in 2016; 36 labs with 3,531 participants in 2021) found effect sizes near zero compared to the originally claimed d = 0.62. The core finding was completely demolished by these failed replications.

Why We Sleep by Matthew Walker contains multiple specific claims with factual errors or significant exaggerations, as documented by researcher Alexey Guzey and subsequent debates. The mortality statistics for short sleep were particularly problematic. But this is different from Willpower—it's not that the underlying science failed to replicate, it's that the book misrepresented the underlying science.

Why Nations Fail by Acemoglu and Robinson makes strong causal claims about institutions and economic growth. There are legitimate academic critiques: the theory struggles to explain China, and the foundational colonial origins study has data quality issues. But the authors won the 2024 Nobel Prize in Economics for this work. The claims are contested in the normal academic sense, not debunked.

Superforecasting by Philip Tetlock reports on forecasting tournament results that have been replicated and extended. The core findings hold up.

These are four different situations. Collapsing them into "has problems" versus "is fine" loses the distinction between "the central thesis was experimentally destroyed" and "there's an ongoing academic debate that sophisticated readers should know about." The taxonomy I settled on:

| Status | Meaning |

|---|---|

| Completely Debunked | Core findings refuted by well-powered replications |

| Misrepresented | Cherry-picked or exaggerated the original research |

| Oversimplified | Nuance lost but directionally correct |

| Contested | Active scientific debate, no clear resolution |

| Validated | Findings hold up to scrutiny |

This is imperfect - some books fit multiple categories across different claims - but it's better than the alternative of either vague ambiguity or false precision.

What the Research Pipeline Can't Evaluate

The model evaluates based on claims about the book and evidence about those claims from the web. It doesn't read the actual book. For these well-known books, there are no shortcomings to this approach. For more obscure books or more subtle issues, the evaluation quality depends on whether someone has already published the critique the model needs to find.

And the search queries are heuristics. Sometimes the model finds the key replication study immediately. Sometimes it misses it. The queries are reasonable, but not exhaustive.

The Broader Research Pattern

I've been thinking about task suitability around LLM-augmented research infrastructure. This pipeline works because:

-

The task is well-scoped. "Evaluate claims in this book against replication literature" is specific enough to prompt for, broad enough to benefit from agentic retrieval.

-

Ground truth exists. There's a fact of the matter about whether a finding replicated. The model is synthesizing documented evidence, not generating opinions.

-

The sources are online. The relevant critiques, replication studies, and meta-analyses are publicly accessible via web search.

-

Human review is tractable. The output is structured enough to audit. You can check whether the model found the right studies, whether the citations are accurate, whether the categorization is appropriate.

2026 is going to be a wild year, since these properties apply across industries from law to medicine and public policy.